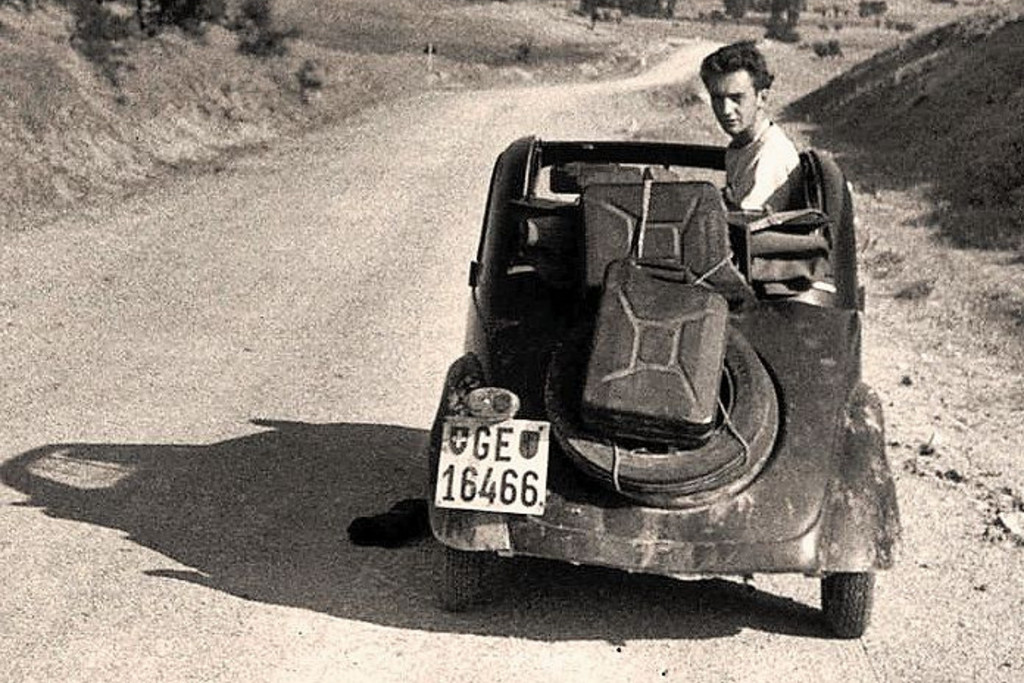

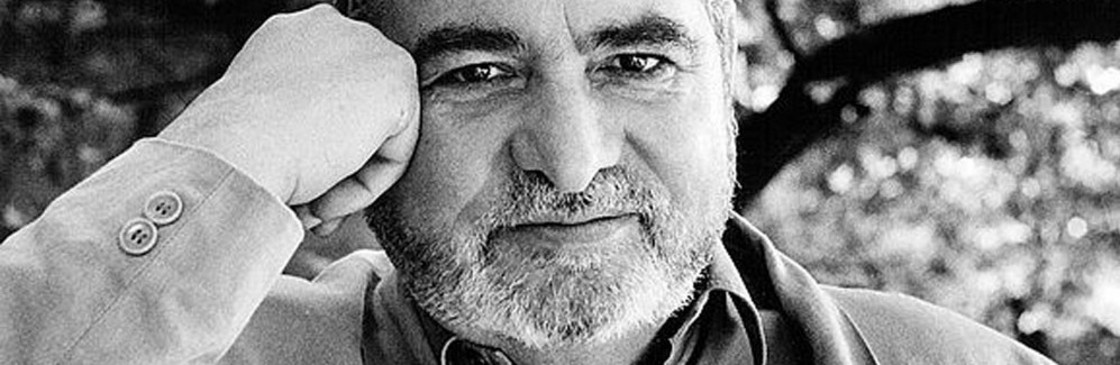

Jürg Federspiel was born in Kempttal on 28 June 1931. In 1961, when he lined up alongside other debutants like Paul Nizon and Peter Bichsel with the publication of a collection of short stories entitled “Oranges and Deaths”, Werner Weber said Federspiel stood out from the pack. Even later, his books stood out not only because of the brilliant research that went into making them, but also for their affinity with the themes of life and death. Having begun with the description of a man who shoots himself dead with a carbine, he continued along similar lines in “Museum of Hate”, published in 1969, a warts-and-all report about a New York in which a young Swiss man first sees nothing but razorblades and is then overwhelmed by visions of death and sexuality.

Federspiel had lived in Paris and Berlin, but when he went to New York in 1967 he was gripped by “complete euphoria”. Without ever breaking ties with Switzerland, he spent part of every year until his death in the city he had evoked literarily not only in “Museum of Hate” but also in “The Ballad of Typhoid Mary”, “The Best City for Blind People”, “Madness & Garbage” and “Voices in the Subway”, never abandoning his central themes of love and death.

“The Ballad of Typhoid Mary” became his most famous book. In this, these themes focussed entirely on the fictional Grisons cook Maria Caduff who, like the genuine historical character Mary Mallon (1869–1938), roamed around New York like an angel of death, spreading typhoid wherever she went, without dying from it herself. Apart from the fact that this unwittingly presaged the dawn of a disease associated with sexuality, AIDS, the book also provided the seed for a trend that is far from over. Dr Rageet diagnosed in Mary “an indifference that sometimes attacks us and now descends upon us as the last and possibly ultimate plague of the soul. A ghost is wandering around. And that ghost is called Hopelessness.”

Ominous foresight can also be found in Federspiel’s most sensual book, “Geography of Lust” (1989), which deals with the spectacular consequences of a tattoo that a Milanese bon vivant named Robusti has etched on the buttocks of the beautiful Laura. An inscription in the sky in the tattoo reads: “The age of shame is finally over. God has forgiven us. Our skin is our clothing. It belongs to us!”

Death was not simply a literary motif for Federspiel, but an existential challenge. Forced to watch as his TB-suffering father turned off his own oxygen supply in Davos in 1949, Federspiel realised: “We can’t contradict the dead. We must seek them out in the restraints we have invented for them.” In 1959, it was his turn to face death when he had to have half a lung removed in order to stay alive, an operation which left him with a certain handicap. In 1997, polyneuropathy and Parkinson’s disease forced him to abandon plans to turn the Davos of his youth into the backdrop for a novel. Love, too, remained yearning rather than fulfilment. The latter proved elusive with both the dainty anti-feminist Esther Vilar (“The Manipulated Man”) and a later relationship which saw him retreat to a village in Thurgau. Zoë Jenny was there to witness his last stay in New York. In “Spätestens Morgen” (2013), she wrote about the sensitivities of a now deeply melancholy Federspiel sitting on a New York park bench in the autumn of 2006. “Four o’clock in the morning is the executioner’s hour,” he told his young fellow writer. It must have been at precisely this time on 12 January 2007 that he sought death unnoticed in the River Rhine in the centre of Basel.

Charles Linsmayer is a literary scholar and journalist in Zurich.

“It was night as I glanced out of the window on the 14th floor of the building. The view of New York and its tens of thousands of lights is truly tremendous and lovely. I wondered whether every light represented a person’s dream to be king for at least one night amid the darkness of millionfold disappointment.”

Extract from “Manhattan and a Boxer” in “American Dreams”

Zurich, 1984

Bibliography: Jürg Federspiel’s books are published in German by Suhrkamp.

Comments