Hunted and misunderstood

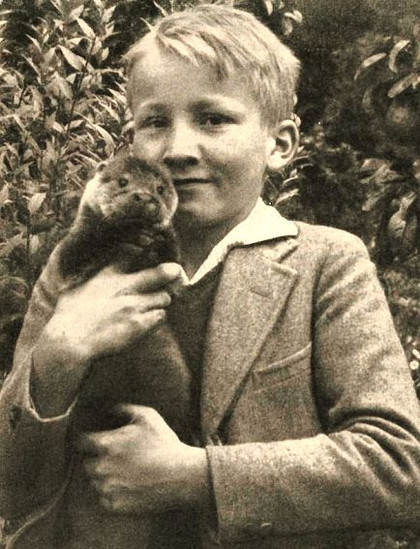

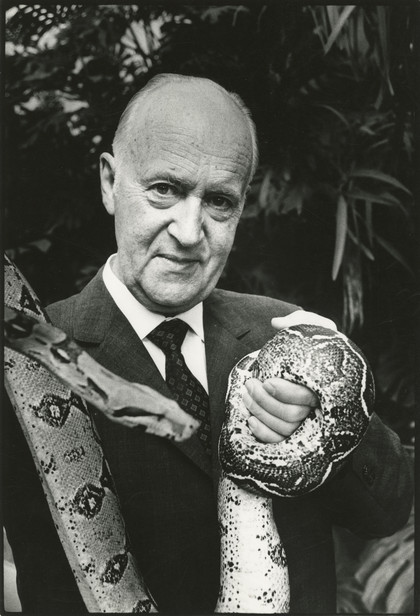

After seeing what had happened to Peterli, Heini Hediger took matters into his own hands. In publications and on radio programmes, he did all he could to highlight the plight of a species that had been unfairly branded as a fish thief. Didn’t otters devour vast numbers of fish and hunt simply for the thrill? No, said Hediger, explaining that the otters at Basel Zoo each consumed 600 grams of food every day – not kilos of fish, as the press had written. Their diet also included frogs, crayfish, rats, mice and waterfowl.

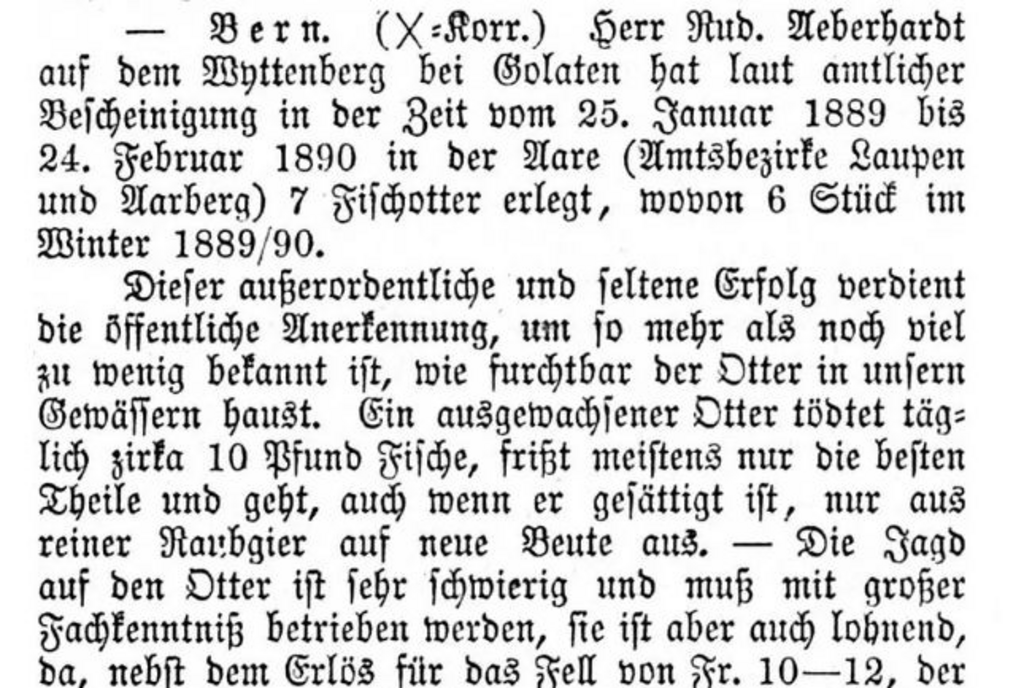

When the otter became a protected species in Switzerland, Hediger concluded that the animal was virtually extinct. He believed that the opportunity to learn more about otters had been squandered. He also had no idea why otters were unable to breed in captivity. Knowledge in this area was limited. Switzerland still had between 80 and 150 otters at the time, divided into a few small clusters in Grisons, on Lake Neuchâtel and on Lake Biel. But despite government measures to protect them, these remaining otters also disappeared. Not only had their natural habitat been destroyed, but pollution had also been an aggravating factor.

Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), a group of man-made, toxic chemicals used in numerous products, had entered the otter’s food chain, building up inside the animal. Consequently, the otters became infertile. Switzerland banned PCBs in 1986, but the last otter died on Lake Neuchâtel three years later. The species was declared extinct in Switzerland.

Comments

Comments :

So aufwühlend und beschämend der Bericht von Peterli für die Schweiz ist, desto positiver werte ich, dass der Fischotter seinen Platz in der freien Wildbahn wieder gefunden hat. Ende gut, alles gut.