Everything is neat and tidy here. All the caravans are clean and well equipped. No rubbish is left lying around, and music is played at a reasonable volume. Freshly washed clothes hang to dry in the sun, and the dogs are well-behaved and kept on leads. You might well think that this is a typically well-maintained holiday campsite.

But you would be mistaken. It is not holidaymakers who are staying in the caravans on Wölflistrasse in Berne. These are the homes of Yeniche travellers who, like those of us who live settled lives, get up early in the morning, go to work, do housework in the evening, remind their children to do their homework, watch television and enjoy a beer. This is not a campsite but simply a car park – without sanitary facilities but with water and power supply. The Yeniche have only just secured this site from the city of Berne and are full of praise for it: “It really is a great facility.”

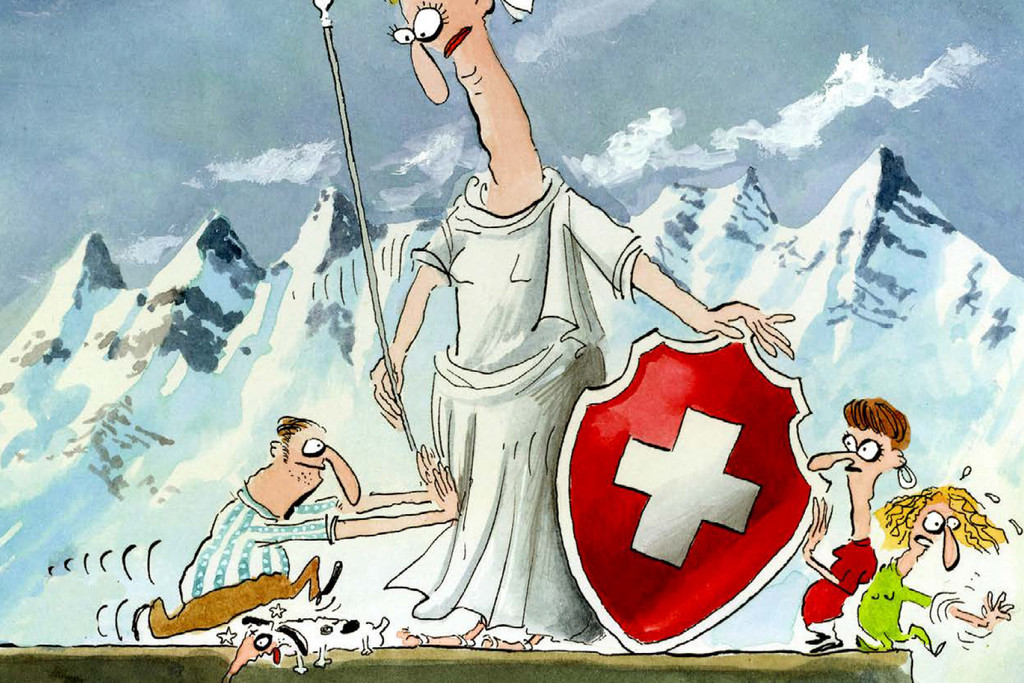

There was nothing great about Berne several weeks ago. The travellers’ patience was running thin as there is still no sign of the residential and transitory sites that have been promised for years. Young Yeniche people vociferously called for these sites to finally be provided because without them Switzerland’s nomadic minority would no longer be able to continue their way of life. On 22 April 2014, they finally occupied parts of the Kleine Allmend site in Berne parking around 80 caravans. Banners highlighted the issue: “lack of sites” – “help” – “we have rights”.

The authorities finally sent in the police, and the situation turned ugly. The police encircled the group, numbered the Yeniche with stickers and water-resistant marker pens, writing directly on the skin, and led them away, terrified small children among them.

The police actually conducted themselves correctly in line with conventional practice and refrained from the use of violence. But when “gypsies” are numbered and led away by uniformed officers, sinister episodes are inevitably called to mind and not just among the Yeniche. “It was awful. It felt as though they were warning us: ‘We’ve still got you gypsies firmly under our control’,” says the traveller Albert Rossier, one of the protest organisers. “That day reminded us that discrimination against our people could resurface at any time.”

Fewer instead of more sites

Rossier may be mistaken. It took just days for the cities of Berne and Biel to offer the Yeniche temporary sites. Both cities expressed understanding for the Yeniche sense of despair over the broken promises and said that they could not be blamed for that. The Federal Supreme Court had in fact decided back in 2003 that the cantons and communes had to take account of the travelling community’s requirements and create more sites. Yet the number of sites has since fallen rather than increased. There is a shortfall of around 60 sites in Switzerland. One reason for this, as Venanz Nobel from the Yeniche association Schäft Qwant explains, is that urban development is reducing the traditional stop-over sites.

Distance from the horror of the past

The controversy brings to light a murky chapter in recent Swiss history - the discrimination against travellers by the state and society until well into the second half of the 20th century, the repercussions of which are still being felt today. Particularly oppressive are the consequences of the “support service for the children of the road” set up by the Pro Juventute foundation in 1926. With the assistance of state welfare authorities, around 600 Yeniche children were removed from their families and placed under the care of the “support service”. Alfred Siegfried, the figure behind the aid organisation, regarded the “break-up of the family unit”, “prevention of the formation of undesirable families” and the “internment of incorrigible persons” as a good way of combating “asocial tribes”. Siegfried, whose theories remained unchallenged for many years, always considered the “gypsies” as “intellectually and morally inferior” and as “vagrants with poor genetic make-up” with a “tendency towards slovenliness and criminality”. He publicly proclaimed in 1964 that a significant proportion of the Yeniche had to be “categorised as mentally deficient”. The persecution only ended in 1973. In 1986, Federal Councillor Alfons Egli apologised for the federal government’s financial contribution to the ill treatment. The federal government set up the Future for the Swiss Travelling Community foundation in 1995.

New courageous generation

The young Yeniche are also familiar with the dark chapter in their history which mostly concerned their grandparents. They nevertheless do not want to portray their generation as victims. They embrace their Yeniche roots, know their rights and duties as citizens and are self-assured. This is not something that can be taken for granted as the Yeniche culture almost died out in Switzerland after the years of persecution. It took years for them to rediscover and re-establish their own identity. Apart from the Yeniche community, quixotic neo-romantics also played a role here. These included the author Sergius Golowin (1930-2006),who believed “cosmic knowledge” lay in Yeniche culture and mediated between the travellers and politicians.

In the course of their journey of self-discovery, the Swiss travellers set up the Travellers’ Society (Radgenossenschaft der Landstrasse) in 1975 and increasingly defined themselves as an independent ethnic minority. Venanz Nobel, who was barely 20 years old at the time, is amazed today at how powerful the Travellers’ Society has become. Still persecuted as “vagrants”, the founders come across as defiant and visionary Yeniche: “A new generation has displayed Yeniche courage in Berne, a generation that once again has lived on the road since childhood.”

No imposition from above

At federal government level, since 1986 the Federal Office of Culture (FOC) has been responsible for the Yeniche minority, their recognition and the protection of their cultural heritage. This is no easy task as the older Yeniche believe much of the repression experienced was brought about by the state. Fiona Wigger from the Culture and Society section at the FOC is aware of this issue: “It is therefore vital that no ‘cultural advancement’ is imposed on the Yeniche from above. It is a question of supporting what the Yeniche themselves want,” she remarks. The emphasis is on the creation of new residential and transitory sites: “Sites are vital to ensuring the continuation of the itinerant way of life. The search for sites is also the most difficult task of all.” Voters in the commune of Thal (St Gallen) rejected a stop-off travellers’ site in May. The conditions appeared favourable as the plot of land in question was provided by federal government as a site for travellers. The rejection of the proposal in Thal “showed us that good will alone is not enough”, says Wigger.

Settled majority

The Federal Office constantly has to confirm that the number of residential and transitory sites is not increasing. Is the site issue really that significant when only a minority of Yeniche are actually on the road? Wigger points out that the Yeniche who are settled or “have been forced to settle” still strongly define themselves as travellers. The emphasis is therefore placed on the lifestyle of the minority.

The Yeniche language is another identity-defining factor. Yeniche was nevertheless primarily a protective language and less a language fostered for its own sake on which the culture was based. Certainly not all Yeniche people speak the Yeniche language, just as not all of them rottle (travel) around in Scharottel (caravans) in search of a Pläri (site). Not all of them schränze (sell goods door to door), let alone boil their Fludi (water) on the Funi (fire).

But ever greater importance is being attached to the language. The Yeniche themselves increasingly highlight that the appreciation and preservation of their language is part of their recognition as a minority. “Whether majority society accepts us as a people also depends on our ability to master our own language,” observed the Schäft Qwant association a decade ago. Wigger explains that the FOC plays a supportive role here and backs projects that document the Yeniche language. The financial contribution is nevertheless modest.

“We are the 27th canton”

Essentially, the question is raised as to whether a few sites would be enough to put right the world of the Yeniche and to declare that the historical failings of majority society are a thing of the past. Daniel Huber, President of the Travellers’ Society, remarks: “It would obviously help redress the situation if we were to obtain more sites.” He also outlines a much wider claim: “We are, in principle, the 27th canton of Switzerland.” The itinerant Yeniche are also citizens. They are all, without exception, registered with a communal authority, are liable to pay taxes there and enrol their children at the local school – the modern Yeniche do not wish to come across as uneducated.

The Zurich-based historian Thomas Huonker, who has been carrying out research into the history of the Swiss Yeniche for years, believes the desire of the Yeniche to be perceived as the 27th canton reflects the essence of all the problems. The historian explains that a completely “normal” level of recognition is far from being achieved as the Yeniche in Switzerland are unable to exercise any rights of self-determination. It is as though the support provided for the Yeniche is granted “as a reward”: “If you are good, then you will get something in return.” A minority’s right to existence must be more than a gesture from the majority.

Huonker believes there is a lack of general appreciation that the Yeniche “do not possess the resources to which they are actually entitled”. All Swiss Yeniche pay taxes regularly. But the principle of “no taxation without representation” does not apply to them. Huonker points out: “They pay taxes but are not represented within the state and therefore remain on the periphery.”

Voting on the destiny of other people

Huonker is clearly aware that the creation of a 27th canton for a “non-territorial ethnic group” is likely to remain a utopian idea. However, this does not release the state from its obligation to strive for better

political integration of the Yeniche. Any marginalising decisions by the majority must at the very least be avoided. He too makes reference to the decision reached in Thal: if the Swiss majority is allowed to vote on the right of existence of a minority, which is also Swiss, at communal level, then the “natural right to exist” is effectively denied to the Yeniche people. Huonker says: “Voting on the destiny of other people is extremely problematic from a constitutional perspective.”

Longings of “ordinary people”

Although the prejudices against the Yeniche continue to have an effect, Huonker has also observed a change in attitudes: “Swiss people increasingly see the Yeniche as essentially people who live and work here and who simply want to be recognised,” he says. Settled “ordinary people” do not feel particularly attached to their home turf, and the nomadic lifestyle is very much en vogue: An itinerant existence for work purposes is seen as a modern way of making a living, and there are lots of amateur travellers who head off for a “transit site”, in other words a second home, in Tuscany, Provence or Berlin.

With their growing recognition as a Swiss minority, there is also an increasing need – even pressure – among the Yeniche to distinguish themselves from foreign travellers. “We are confederates,” underlines Mike Gerzner, the young President of the Movement of Swiss Travellers. He says this to distance himself from the foreign Roma who often pass through the country from France. Sites are therefore required for Swiss travellers who visit their customers as door-to-door salespeople and tradesmen, explains Gerzner, and separate sites are needed for the often large groups of Roma passing through.

Locals versus foreigners

The emphasis on the national aspect is securing the Yeniche growing support from conservative-minded factions who were previously very critical of them. SVP National Councillor Yvette Estermann has become something of a political advocate of the Swiss travellers. She is calling for greater protection of the “domestic Yeniche” from the federal authorities against the incoming Roma. Racism expert Georg Kreis believes the distancing of the Swiss Yeniche from their “foreign brothers and sisters” is also a “cause for reflection”. It underlines once more “that minorities discriminated against – not least owing to pressure from the majority and a compulsion to distance themselves – tend to pass on the discrimination they have experienced themselves to others”. Perhaps it is in fact much more banal than that and the Yeniche and Roma are getting in each other’s way because it is becoming increasingly crowded on their sites. Foreign Roma have only been allowed to enter Switzerland since the mid-1970s. As previously mentioned, the number of sites has since fallen instead of increased.

No longer like refugees

Claude Gerzner, also from the Movement of Swiss Travellers, is very optimistic. He has seen a change for the better in recent months: “Far less prejudice now exists. We feel much less like refugees in our own country.” If a Yeniche family turns up with their caravan today, “everyone now knows that we’re very much normal people. Just people on wheels”. Venanz Nobel is somewhat more restrained. It is mainly travelling Yeniche who are enjoying better recognition: “We will have achieved our goal when the Yeniche as an entire ethnic group – including both settled and travelling Yeniche – obtain recognition.”Back to Wölflistrasse in Berne. What do people here think about the debate on Switzerland’s treatment of the Yeniche minority? A powerfully built, bearded man standing next to his caravan takes a deep draw on his cigarette, looks vaguely towards the Alps and does not really address the question. He has no use for intellectual rigmarole. He feels the urge to leave. He suddenly decides: “Come on, Claudia, let’s get going!” The couple start to pack. He wants to leave immediately. He does not want to become like the “stationary Yeniche” who have had “travelling driven out of them”. Where is he heading? “Perhaps to Ticino or to Central Switzerland – we’ll see.”

Marc Lettau is an editor with “Swiss Review”

Yeniche, travellers, Roma

The Yeniche are an ethnic group in their own right with their own language and specific way of life and of making a living who primarily live in Switzerland, Germany, Austria and France. The Yeniche population stands at around 35,000 in Switzerland. The establishment of modern states, beginning in the 17th and 18th centuries, with rights of citizenship and domicile geared towards a settled population had a major impact on the Yeniche. It meant that a nomadic lifestyle became an issue. Like the term “gypsies”, the term “travellers” was also subsequently used in a pejorative way: travelling came to represent an unsettled, slovenly way of life. This notion is inaccurate in relation to the Yeniche in Switzerland. Most Yeniche in Switzerland are settled, with an estimated 3,000 to 5,000 living a completely or partially nomadic lifestyle. During the modern period of state formation, the Roma, an ethnic group who migrated to Europe from the Indian subcontinent in the 9th century, also came under pressure in Europe. From a Swiss perspective, the Roma are primarily seen as a people passing through from south-eastern Europe and France and are often viewed in a negative light. There is little awareness of the fact that thousands of settled Roma live in Switzerland without being perceived as such. They have migrated to Switzerland from south-eastern Europe in particular. (mul)

Comments