Suddenly, it just stopped: The drilling head of a tunnel boring machine got stuck in a tricky geological zone near Moutier. It took two years until the behemoth could be dug free again in 2005, at great expense. The additional cost amounted to 158 million francs. Last April, construction work was finally completed on the Transjurane, the A16 motorway from Biel to the canton of Jura. It had taken almost 30 years and cost 6.6 billion francs. The road not only connects the canton of Jura with Bernese Jura and central Switzerland, it also links the Swiss and the French motorway networks.

In this region, however, what separates is sometimes stronger than what connects. And the small town of Moutier was not just a hard geological nut in 2005, it was an epicentre of the Jura conflict. Even though the conditions in Moutier in the 1970s cannot be compared to those of Belfast in Northern Ireland, the situation in many parts of the small town in Bernese Jura was extremely tense.

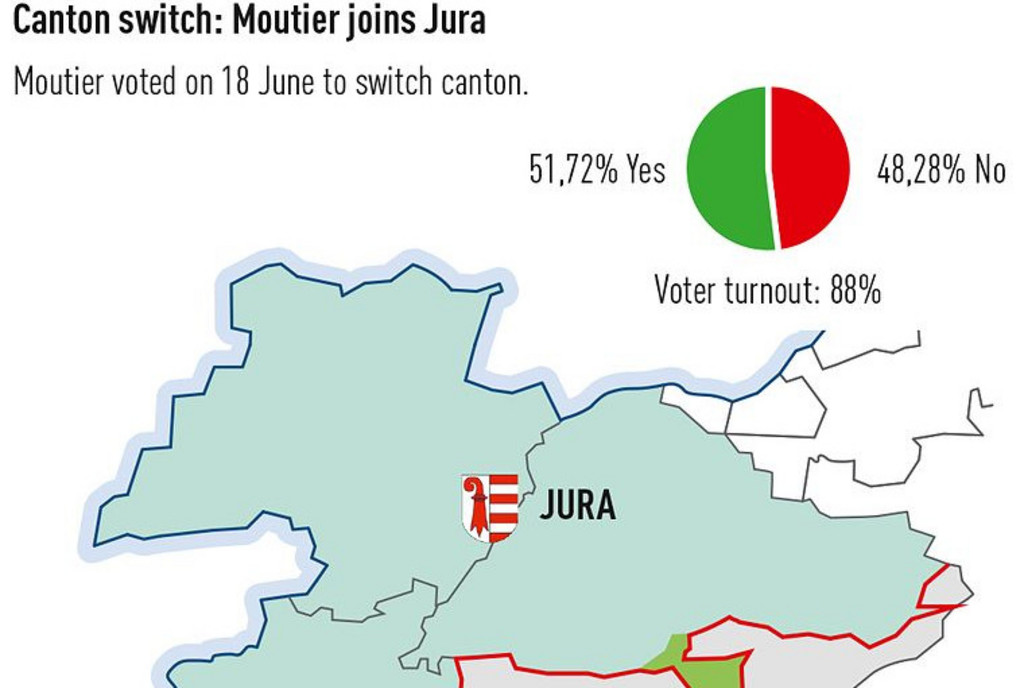

It is there that one of the last significant chapters of the Bernese-Jura conflict has now been written, in a civilised manner without violence. In a historic referendum, the community decided on 18 June to turn its back on the canton of Bern, and join the canton of Jura. Nevertheless, the coming years will still see wrangling over organisational and administrative matters, in issues regarding division of property for example. This process could take years. And thereafter, the voters of the cantons of Jura and Bern as well as the National Council and Council of States must give their blessing to the change of canton.

Laborious, multi-stage process

The Moutier referendum is a key part of – what is intended to be – the definitive solution to the most difficult territorial conflict in Switzerland of the 20th century. After the creation of the canton of Jura in 1979, the situation in the divided region did not calm down completely, rather, it was seriously strained. The separatists were not satisfied because only the three northern districts of Porrentruy, Delémont and Franches-Montagnes were to form the canton of Jura; the three districts of Moutier, Courtelary and La Neuveville in the south wanted to stay in the canton of Bern. This led to the establishment in 1994 of the Inter-Jura Assembly (AIJ). The work of the AIJ resulted in an agreement between the cantons of Bern and Jura in 2012. This provided for a multi-stage procedure with regional and local referendums. First of all, voters in the cantons of Jura and Bernese Jura were able to decide whether they wanted to establish a Greater Canton of Jura. The Bernese-Jura voters said no in 2013, those in the canton of Jura said yes. As there was no consensus between the sides, the project could not be pursued. The second stage enabled individual communities, if they wished, to decide about switching to the canton of Jura.

New oil on the fire or new pragmatism?

Following the municipal referendums in Bernese Jura, will this really spell a definitive end to the Jura conflict? The answer is yes, at least from an institutional perspective. This is because the cantons of Bern and Jura undertook in the 2012 Jura Agreement to consider the issue solved as soon as the multi-stage referendum procedure is completed. It is another question altogether whether all politicians see things the same way. In a democracy, any topic can be rolled out again. Just after the Moutier referendum, for example, the Mouvement autonomiste jurassien (MAJ) announced it was time to seek “new ways” of restoring Jurassian sovereignty across the whole of the territory. In other words, the separatists want the whole of Bernese Jura. In the Grand Council of Bern, more and more voices are being heard questioning the guaranteed position of Bernese Jura in the cantonal government, or at least wanting to dilute it. There is also talk of reducing the twelve Bernese-Jura seats in the Grand Council since this part of the country has become smaller. This all bears potential for new conflict.

But Sean Müller, an authority on the Jura issue and lecturer at the Institute of Political Science at the University of Bern, is convinced that “nobody really wants to rekindle the conflict”. In terms of cantonal borders, the issue is resolved. In Bernese Jura all the referendums have demonstrated that there is no majority support for a complete switch of canton. “And all parties, including the separatists and the militants loyal to Bern, have become pragmatic and got used to the dialogue as part of the Inter-Jura Assembly and other bodies,” Müller , tells the “Swiss Review”.

Dick Marty, former state prosecutor in Ticino, former FDP member of the Council of States, and a man in demand internationally for delicate missions, played a significant role in resolving the problem. He has chaired the Inter-Jura Assembly since 2010. To “swissinfo” he said: “We used the full range of Swiss democratic means at our disposal to resolve this conflict,” primarily the various referendums at all levels of the country. Marty is convinced that the time-consuming process was a helping factor in “solving a problem that elsewhere under the same conditions could suddenly have slipped into armed conflict”.

“Foundling from olden times”

According to Sean Müller, the most important milestone was the willingness of the canton of Bern to launch the transition process with an open mind. That was back in 1970, when the voters in Bern agreed to a constitutional amendment that paved the way for a multi-stage series of referendums in Jura. It led eventually to the establishment of the canton of Jura. “Giving a minority this opportunity was very generous and respectful,” says Müller. Yet before that, things happened “that were not always consistent with the normal picture of Swiss politics”, for instance, after voters in Bern in 1959 rejected an initiative from the political movement Rassemblement jurassien for a Jura plebiscite, the separatists in the 1960s resorted to increasingly radical methods. For example, the Bern Day at the 1964 Expo in Switzerland was disrupted, and the Bern Grand Council bricked up. There were also explosions and arson attacks. Street fighting broke out in Moutier in the middle of the 1970s between armed separatists and the Bern Cantonal Police.

Historian Jakob Tanner delves back even further and describes the Jura conflict in his book “History of Switzerland in the 20th Century” (Geschichte der Schweiz im 20. Jahrhundert) as a “political foundling from olden times”. When Jura was assigned to the canton of Bern at the Congress of Vienna in 1815, a French-speaking, Catholic area came under the control of a German-speaking Protestant canton. Thereafter, those in northern Jura felt short-changed by Bern, which invested little. Road and rail infrastructure was inadequate. At the same time, the Jurassians with their French-speaking culture sensed a lack of respect. Those in southern Jura, on the other hand, experienced increasing industrialisation coupled with significant immigration of German-speaking Swiss. This lent the conflict a linguistic/ethnic component alongside the historical, religious and economic causes.

What is more, for historian Clément Crevoisier, the Jura question had a significant symbolic influence on Swiss politics from the 1950s to 1980, according to an interview in “Der Bund” newspaper. “The Jura conflict reflected the discord between the progressive, forward-looking movement of the sixties and conservative Switzerland,” he says. Conversely, notes Crévoisier, “the separatists were able to draw on the spirit of change that prevailed in the 1960s and 1970s.”

A non-conformist constituent state?

The canton of Jura also stems from a time in which political visions were accorded a different weighting than today. The Historical Dictionary of Switzerland still considers the youngest canton to be “a progressive and non-conformist constituent state”. For political scientist Sean Müller, however, the general voting behaviour in the canton of Jura paints an inconsistent picture. In socio-political issues, where religious attitudes play an important role, Jura is rather conservative. As regards their stance on openness, migration and foreign policy they are labelled “progressive” – but in this way they are no different to Romandy as a whole and the large Swiss-German cities. And the composition of the political authorities in the canton of Jura is now roughly the same as the Swiss average. Jura could be labelled non-conformist in the sense that the right of foreigners to vote was included in the constitution from the very beginning, for example.

From an economic perspective, however, the canton of Jura is not a growth driver. It regularly comes last in terms of competitiveness, and with regard to financial equalisation for the cantons it is one of the largest recipient cantons per capita. The expectations became much more ambitious upon the establishment of the canton, says Müller. But the starting situation as a peripheral region relatively far from the economic hubs was difficult from the outset. The newly completed Transjurane motorway does raise hopes of some economic impetus for the structurally weak region. However, says Sean Müller, a motorway can have the opposite effect that more people commute to work outside the canton.

Just like most similar cases, and generally speaking in politics, the Jura conflict was never just about strong rational arguments, there was always a lot of emotion. Even the somewhat anachronistic dispute today about the “right” cantonal affiliation hovers somewhere between a right to self-determination, identity issues and ethno-nationalism. And even if the canton of Jura will probably never stretch down as far as Lake Biel, and the conflict will someday be confined to history, the “Rauracienne”, the official anthem of the canton of Jura, will probably still say:

“From Lake Biel to the gates of France / Hope ripens in the darkness of the towns / From our hearts sounds a song of deliverance / Our flag waved on the mountains / You, who care about the fate of the fatherland / Break the chains of an unjust destiny!”

200 years of the Jura conflict at a glance

1815: At the Congress of Vienna, the territory of the former Prince-Bishopric of Basel is given to the canton of Bern. This part of Jura had been a French département since 1793. The first conflicts between those loyal to Bern and the Jurassians took place after 1815.

1947: The Bern Grand Council refuses to let Jurassian state-council member Georges Moeckli head up the Department of Public Works and Railways, because he is a French native speaker. The Jura conflict begins to escalate.

1950: The canton introduces French as the second official language. The Jurassian districts also receive two guaranteed seats in the cantonal government.

1963: Establishment of the young separatists’ organisation known as Béliers, which carries out various provocative actions. Explosions and arson attacks are attributed to the Jurassian Liberation Front (FLJ).

1970: The people of Bern agree to a constitutional amendment that paves the way to a multi-level series of plebiscites.

1974: The people of Jura vote for a separate canton. But this canton will only comprise the three northern districts, because the three southern districts of Jura want to stay with the canton of Bern.

1978: The people of Switzerland and all cantons agree to the establishment of the canton of Jura with an 82.3 percent majority. One year later, the République et Canton du Jura joins the Swiss Confederation as its newest entity.

1994: As the Jura conflict continues to smoulder, an Inter-Jura Assembly is set up to work out proposed solutions. This body recommends holding referendums on the reunification of Jura.

2012: The cantons of Bern and Jura reach an agreement to end the Jura conflict once and for all. The agreement provides for a multi-stage procedure with regional and local referendums.

Comments

Comments :

De todas maneras es bueno evitar un Québec suizo.

Depuis une vingtaine d'années j'habite la France, je suis donc un double-national, acquis par mon épouse de souche française. Je constate avec joie, que la Suisse reste mon pays, j'en suis fier Mes origines valaisannes remontent à la guerre de Marignan 1515. ma branche hélas s'éteindra avec moi.....

Un pour Tous, Tous pour un est toujours bien présent, la preuve est là, par cette création du canton du Jura.

C'est une leçon de démocratie, que la Suisse donne à l'Europe au Monde durant ce temps troublé, où bien des valeurs sont contestées. Que la Suisse reste vigilante, bien sur ces gardes. Rien n'est acquis définitivement.

la seule ville de Moutier est-elle concernée (d'autres communes avoisinantes, comme Bévilard...) ?

Cordialement