Switzerland and its watchmakers – entire libraries could be filled with books on this subject. Famous inventors and horologists include Abraham Louis Breguet, who designed the tourbillon in the 18th century, and Adrien Philippe, who invented the winding crown in 1842. There were also talented watchmakers who chose to pursue different paths. Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, for example, was the son of a watch face enameller from La Chaux-de-Fonds. He learned how to engrave cases but in 1905 decided to focus on the visual arts and moved to Paris. He enjoyed a successful international career under the name of Le Corbusier.

Watchmaking was, of course, not originally a Swiss craft. Huguenot refugees from France brought it to Calvinist Geneva. It can even be dated back to a particular year. In 1587, the city council granted the Frenchman Charles Cusin citizenship at no charge on the sole proviso that he taught his trade to the local goldsmiths. Cusin was also courted by the Duke of Navarre, who later became King Henry IV of France, on account of his craftsmanship. The master craftsman soon vanished from Geneva, taking with him a large sum of money advanced by the government. Horology nevertheless continued to flourish. A century later, there were a hundred watchmakers employing three hundred apprentices.

Every manufacturer had their own secret

From the outset, every watchmaker cultivated stories of their own little production secret and legendary status. Even in the 18th century, historians referred to them as artists rather than craftsmen. One such artist, who was self-taught, was the founder of the Neuchâtel watch industry. This was Daniel Jeanrichard, who grew up in a hamlet called Les Bressels near Le Locle. Jeanrichard’s father is presumed to have been a smith and his son is believed to have undertaken an apprenticeship as a goldsmith. Where he did this and what he intended to do with these skills in a place like Les Bressels is unclear from the historical sources.

In any case, in 1679, a widely travelled horse trader by the name of Peter visited the smithy in Les Bressels. He had a pocket watch from London with him which had got broken on the journey. When the horse trader saw some of the work produced in the smithy by the young apprentice Daniel, he gave him the watch and the youngster managed to repair it. What is more, the 14-year-old conceived the idea of making a similar watch.

Such craftsmanship was previously “completely unknown” in the mountains of Neuchâtel, wrote the historian Frédéric-Samuel Ostervald, who, in 1765, produced a book on the principality of Neuchâtel, which still belonged to Prussia at the time. Daniel Jeanrichard spent a year working on the fine tools required and then on the springs, the case, the fusee and the balance. He put the watch together over the next six months. This was the first timepiece to be made in the principality of Neuchâtel.

Low production costs

Ostervald assures us that all this information is “absolutely correct” and “borne out by several artists”. Indeed, in addition to several rather clunky watches furnished with the JeanRichard stamp, one of his sketchbooks also survived and his name is documented in Le Locle from 1712 onwards. The sources indicate that he had begun to produce more watches and to recruit apprentices from the lowlands. He also taught his trade to his brothers and later to his sons. Daniel Jeanrichard – his statue today stands in the centre of Le Locle – is also credited with inventing a device for the manufacture of cogwheels, though this was more likely copied from a competitor in Geneva.

Watchmaking would certainly have been much cheaper at that time in the villages than in Geneva, not least because production there was not hampered by any guild laws. By 1765, when Ostervald’s book was published, 15,000 gold and silver watches had already been exported from the mountain valleys of Neuchâtel. Thirty years later, the figure reached 40,000 pocket watches, joined by, in Ostervald’s words, a “large quantity of simple and composite clocks”. The villages of La Chaux-de-Fonds and Le Locle grew into small towns, each with over 5,000 inhabitants, and an estimated 12,000 people made a living from the watch industry in the region.

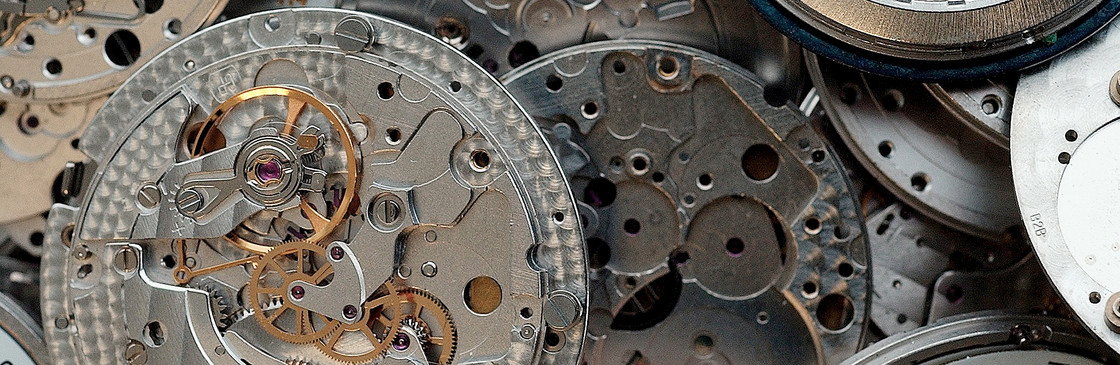

Watchmaking was still a cottage industry. There was no central production facility. Manufacturing was divided into small work processes and assigned by the watchmaker to specialist craftsmen. These people usually worked at home on a farm or in a provincial workshop, received piece-rate pay and worked on demand with material supplied by the client. Only at the very end were the individual components assembled by the watchmaker.

A specialist for every work process

It was a fragmented, solitary and silent trade that these artists practised in the valleys around La Chaux-de-Fonds and soon also further south in the Vallée de Joux and the Bernese Jura. They hardly spoke whilst working, breathed carefully and sat with tremendous self-discipline on adjustable wooden stools at high windows. The slightest vibration could disturb their work. Despite the high degree of routine, it remained a profession that required thought. The watchmakers soon became the aristocrats of the workforce, at least that is how they saw it. And their ranks were constantly swelled. Production increased ten-fold between 1830 and 1850. They organised themselves politically, were left-leaning, however not Marxist but instead libertarian. They were among the founders of the anarchistic Anti-Authoritarian International that held its first conference in the Bernese Jura village of Saint-Imier in 1873. They stood for individual freedoms and fought against paternalism. And as long as their production was better and less expensive than everyone else’s, they had nothing to fear from mechanisation which had already begun in the USA and had crippled the strong competition from Great Britain.

The competition in the USA

The World Expo opened in Philadelphia on 10 May 1876, showcasing American industry. The delegates from the watchmaking cantons returned both shocked and inspired. Jacques David from Saint-Imier described in a report how he had also visited the factories of Waltham Watch, Elgin Watch and Springfield Watch on his trip. He wrote that people needed to acknowledge that the Swiss industry had been overtaken. He brought American watches back with him to show to Swiss industrialists. These timepieces were not just cheaper but at least as good as their own.

The large factories in Waltham, Massachusetts, and other sites in the USA no longer operated on the basis of the pre-industrial workshop system but instead used modern production facilities where hundreds of workers put together watches from standardised components using machinery. Similar factories needed to be built in Switzerland, urged David, who was himself employed as an engineer at the Longines watchmaking workshop. “If they are not built here, then they will be constructed in the USA and there will be nothing left for us within a few years as the Americans are already selling their watches in our markets, in Russia, the United Kingdom, South America, Australia and Japan,” he observed in his report.

The first crisis

David was proven right. The Swiss watchmaking industry plunged into a deep recession in the 1870s. This was the first of three severe downturns, each of which saw the industry teeter on the brink of collapse. The Swiss had previously conquered market after market, whether it be Russia, where Heinrich Moser from Schaffhausen monopolised trade as early as in 1848, China, where Bovet from the Val de Travers dominated the south and Vacheron Constantin from Geneva the north, or Japan, where the Neuchâtel manufacturers established themselves soon after the opening-up of the country. This triumphal procession now came to a halt. Three quarters of all timepieces sold worldwide still came from Switzerland in 1870. Over the years that followed, however, cheap American products followed by industrially manufactured German ones even penetrated the Swiss market!

The Swiss nonetheless managed to set up their own mass production remarkably quickly. The factories were no longer located in the mountainous parts of the Jura, which were unfavourable for transport, but instead in the region where the Jura meets the Central Plateau. The new watchmakers were no longer the “artists” of the past – these did continue to exist in the mountains but what they produced was now deemed expensive luxury goods. Unskilled workers were also taken on in the factories. A typical industrial working class emerged in Biel and Grenchen, two new centres of the industry. The workers organised themselves and elected left-wing municipal governments. Industrial disputes, usually over wages, took place on an almost weekly basis. The number of factories increased ten-fold between 1882 and 1911, with wristwatches produced for the first time in addition to pocket watches – the company Girard-Perregaux in La Chaux-de-Fonds was among the pioneers. Horology had arrived in the modern age.

Japanese competition

The second crisis that threatened the survival of the industry occurred immediately after the First World War. Sales to Germany and the countries of the former Austro-Hungarian Empire ground to a halt and exports to the new Soviet Union also ceased. The first Japanese watches competed for customers in East Asia and Latin America, and many countries, such as Spain, levied high import duties. Switzerland’s main customer was now the USA, where it continued to face fierce domestic competition. By spring 1921, the export figures had been halved compared to the pre-war period and the number of unemployed watchmaking workers had risen from zero to 25,000. Prices were eroded and a recession took hold, which also hit the textile and machine-building industries and lasted intermittently into the 1930s.

The high-end luxury segment was barely affected. Rolex, originally established by a Bavarian as an import company for Swiss watches in London, for example, performed remarkably well: a waterproof watch called the Oyster – which remains a classic model to this day – was launched in 1926. LeCoultre in the Vallée de Joux was also doing brisk business. In 1929, the company unveiled the world’s smallest watch weighing less than a gram and, in 1931, the legendary Reverso sports watch with a case that could be swivelled by hand so that the glass faced inwards to protect it.

However, the manufacturers of cheaper goods everywhere now had to adapt. The empty factories were to be filled with industry more resilient to downturns. At the start of the 1930s, the left-wing municipal government in Biel financed the establishment of an automotive factory belonging to the US group General Motors to provide employment for the workers.

At the same time, the Société Suisse pour l’Industrie Horlogère (SSIH) and the Allgemeine Schweizerische Uhrenindustrie AG (ASUAG) emerged, two large firms supported by the Swiss Federal Council, which combined several companies or contractually obliged them to cooperate. From 1941, they enjoyed a national monopoly on the manufacture of watches, while keeping the production of the individual brands separate. Under a “watch statute”, the sector was organised as a cartel and minimum prices acquired the force of law. This also aimed to ensure the survival of small companies.

It was essentially the state that intervened this time by regulating imports and exports, making the foundation or expansion of watch factories subject to authorisation until the post-war period and thus establishing decentralised structures. The disappearance of further foreign competition both during the Second World War and as a result of the subsequent division of Europe benefited the Swiss and led to an upturn.

It was nevertheless not long before the next severe crisis hit. History seemed to repeat itself in the 1970s. The Swiss again appeared to have been overtaken by technical advancement, and the competition was once again not just cheaper but also better. This time the recession – made worse by the oil crisis – lasted for over 15 dramatic years. Half of the companies disappeared from the market, and over half of all jobs were lost.

In the golden age of the economic boom after the war, two-figure dividends were regularly paid on the share capital. Exports had risen from 25 million watches in 1950 to over 80 million by the mid 1970s. The cartel of the pre-war period fell apart in the 1960s but, with the large trusts SSIH and ASUAG, the peculiarly Swiss arrangement survived: The individual companies were associated with one another but were at the same time competitors.

Emerging from the crisis with quartz and luxury goods

The dollar plummeted in the 1970s and export prices increased enormously without revenues rising. The Japanese and the Americans not only produced far less expensive watches from much larger factories but also came up with a completely new technology – the electronic watch with a quartz movement. The expertise required had existed in Switzerland since the 1960s but had never been followed up.

SSIH and ASUAG soon faced bankruptcy. Companies like Omega and Tissot belonged to SSIH. Aside from a few luxury brands, all watchmakers purchased their movements from ASUAG. The two ailing conglomerates were combined in a spectacular merger in 1983. Many people believed this was a “last-ditch attempt” to save the watch industry.

It was precisely at this point that the most recent successful chapter in the great Swiss watchmaking saga began. The key figure in the new company was Nicolas G. Hayek. He was a management consultant and very familiar with streamlining measures. He argued that although the Swiss market share of international business had fallen below 10?%, this was only in terms of units. If revenues were considered, Switzerland had a 30?% share and as much as 85?% in the luxury watch segment. Against a background of Swiss despair, Hayek, who was from Lebanon, contended that the watch industry was a “sleeping giant”.

He pursued a two-pronged strategy. On the one hand, he launched the inexpensive quartz watch Swatch, consisting of just 51 components and manufactured by machinery. It achieved cult status over the forthcoming decades with its pop designs. On the other – marketing is everything – the traditional legendary status of the Swiss luxury watch, of watchmaking artists, as Frédéric-Samuel Ostervald had once described them, was revived. The strategy pursued by Hayek, who died in Biel in 2010 aged 82, was successful. His children and grandchildren in charge of the Swatch Group still announce new record sales figures each year.

Stefan Keller is a journalist and historian. He lives in Zurich.

Karl Marx’s description

In the mid 19th century, Karl Marx took a look at the industry in the Swiss Jura. He saw an “immense number of detail labourers”, who did not correspond to the idea of the modern industrial proletariat and whose professions he listed almost breathlessly on half a page: from “ébauche makers, watch spring makers, watch face makers, spiral spring makers, jewel hole and ruby lever makers, watch hand makers, case makers, screw makers, gilders with numerous subdivisions” to “steel polishers, cog polishers, screw polishers, figure painters and dial enamellers”. It took 54 different work processes to produce a watch in 1830. In La Chaux-de-Fonds, 67 different jobs carried out in different locations were distributed between 1,300 workshops and numerous households.

Apprentice watchmaker Jean-Jacques Rousseau

The most famous child of a Swiss watchmaker is Jean-Jacques Rousseau from Geneva who gew up without a mother and whose failed father apprenticed him to an engraver. Rousseau’s training as a timepiece engraver ended in 1728 when he turned his back on his quick-tempered master and the austere city at the first available opportunity. At this time, watches were still the most important source of income for the municipal republic of Geneva. Isaac Rousseau, his father, had lived in a Geneva colony in Constantinople from 1705 to 1711, working as a watchmaker to the Seraglio. Timepieces from Switzerland were already being sold worldwide. The Geneva traders had branches everywhere, including the Bosphorus, Asia Minor, Russia and the Indian Ocean. The philosophical oeuvre later produced by Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the watchmaker’s child who went astray, is today regarded as a bedrock of modernity.

Comments

Comments :

A good story on business needing to innovate to meet market demands, with a long term perspective over 100's of years.