The seat of Swiss national government is ideally positioned as far as beer goes. Anyone who dines at the Galerie des Alpes restaurant in the Federal Palace will not only see the Alps but also have an unobstructed view of the brewery site at the foot of the Gurten mountain, home to the traditional Bernese “Gurten” beer. However, it is not served in the Federal Palace despite the view. Thirsty MPs and Federal Councillors have the choice between other local beers from Burgdorf and Einsiedeln. The brewery in Gurten has actually been consigned to the past. Today the site houses fantastic residential accommodation and innovative companies. The brewery founded in 1864 quenched the thirst of the federal capital for over a century. The company then got caught up in an economic downturn. In 1970, it was taken over by the Feldschlösschen Group, the largest brewery in Switzerland. This company currently brews a beer called “Gurten” at its company headquarters in Rheinfelden, Aargau.

This story typifies the general situation. It has been much worse elsewhere than in stately Berne. In Fribourg, the collapse of the Cardinal brewery, which was established in 1788, sparked a major crisis in the canton. When Cardinal closed down after struggling for years, Fribourg’s government at the time was “shocked” and its president Beat Vonlanthen expressed “deep sadness” at the loss of something that belonged to the canton and symbolised its own economic history. Cardinal only lives on as a name – on Rheinfelden bottles.

“The last Eichhof”

The concentration of the beer market alluded to in these two examples was unprecedented by Swiss standards. It essentially goes back to the collapse of the Swiss beer cartel and eventually also affected the big players. Feldschlösschen AG initially quenched its own thirst through many acquisitions of regional breweries. However, in 2000, Feldschlösschen itself was taken over by Carlsberg, the Danish beer multinational. Heineken, the Dutch brewery group, was also shopping in Switzerland at the same time. The Grissons beer “Calanda Bräu”, for example, is Dutch strictly speaking. “Eichhof” beer from Lucerne is also part of the Heineken empire. The futility of taking a stand became evident in Lucerne. Students from the Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich launched a computer game at the time called “The Last Eichhof”, the aim of which was to prevent a hostile takeover with lots of shooting. It was all in vain, but grumblings about the globalisation of the beer market became louder.

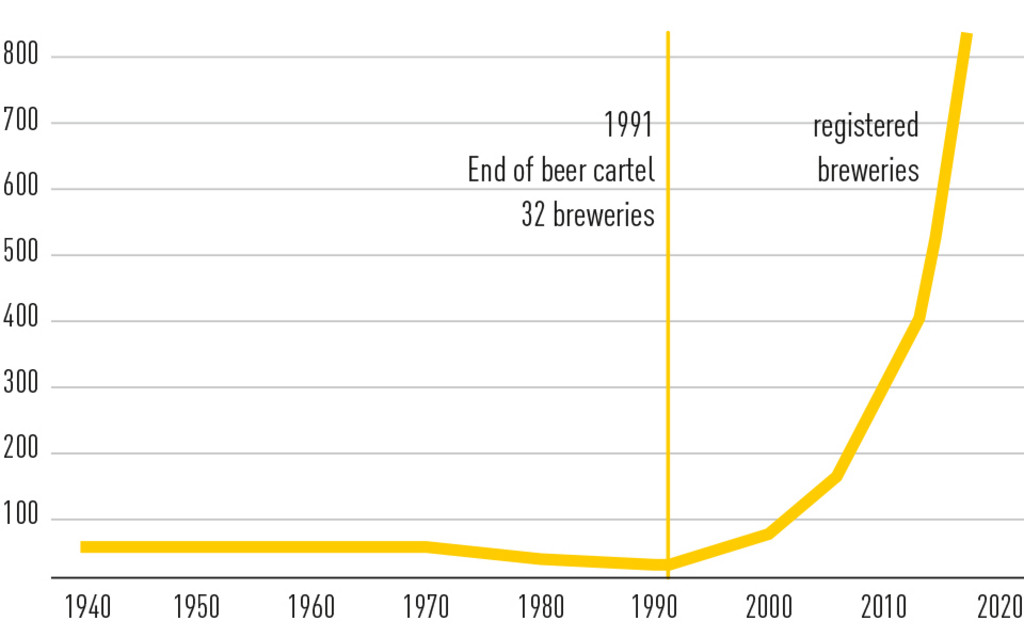

Today, a generation on, the picture is completely different. Over 60 % of the beer consumed in Switzerland comes from breweries controlled by Carlsberg (Feldschlösschen) and Heineken (Eichhof, Calanda). However, hundreds of small-scale setups and microbreweries have emerged to take on the global multinationals. While Switzerland had just 31 operational breweries in 1991, there are over 900 today. No other country in the world has such a dense concentration of breweries in relation to its population. All the niche players are shaking up the market with an estimated 5,000 different beers.

From “Öufi” to “Sierrvoise”

Local patriotic sentiment seems to have surfaced across the country. Solothurn today mainly drinks “Öufi” beer and extols the virtues of number 11 which is celebrated as the town’s special number (“öuf” means “eleven”). In contrast, Sierre swears by “La Sierrvoise”. Burgdorf espouses the local brewery’s slogan of “beer needs a home” and willingly backs this up through its drinking habits. The small town now has a second notable brewery in Blackwell. There seems to be plenty of room in the new homes of beer. Local markets are turning into micro-local ones. Every district has its own beer.

Adrian Sulc, a business editor and long-standing observer of the trend, believes the local patriotism has to be put in perspective: “Most people drink local beer because they like their local brewers and not due to their political outlook.” A general trend can be identified: “Because globalisation is bringing consumer goods from all over the world to our supermarkets, we are suddenly taking an interest in local products.” However, this is not just resulting in more “beer from here” but also more vegetables grown in the region, more bread from the local bakery and more cheese from the area. As far as beer is concerned, he points out: “There would probably still have been a boom even if the beer cartel had not broken up.”

A very colourful scene has emerged. This ranges from unpretentious do-it-yourself recreational brewing and beer-swilling humour to an appreciation of a tradition of craftsmanship. An extremely high number of small-scale setups and microbreweries are clearly experimental artisan enterprises. They produce beverages which are very different to standardised industrial beers.

Tiny universe inside the bottle

What is inspiring the new Swiss brewers? “Swiss Review” singled out the Brauerei Nr. 523 brewery which operates under the rather cryptic name of 523. The initial response to our enquiry was a refusal in itself: We are “rather introverted and therefore not ideal for the press”. That may well be true. The Köniz brewery, based in an old file factory, avoids all ostentation. Malt and hops are more important to it than marketing and merchandising. Even its beer labels are extremely understated. And although the local media all over Switzerland celebrate every new local brewery with great excitement, silence reigns as far as 523 is concerned. The small team – Sebastian Imhof, Nadja Otz, Tobias Häberli and Andreas Otz – do not shout about what they do from the rooftops.

What follows is an eye-opening insight into life inside a microbrewery. 523 beers are also produced for a very well-defined market. Simply being “local” is not enough, says Andreas Otz. 523 obviously samples hops produced in the region. “But the world would become too narrowly confined if we only used what grows on our doorstep.” Otz understands the concept of beer as a homeland-promoting “anti-globalisation beverage”. But when the team make beer, they experience “the positive aspects of globalisation”, he says. If they hear about a local farmer in Seattle experimenting with new hop varieties, they can contact him directly, buy from him and brew and launch a beer that uses the new variety. In this way, globalisation also enhances local products.

The 523 brewers use a range of flavours, aromas and sensory stimulation from all over the world and pursue “their vision uncompromisingly”, Otz says. How can, say, the taste of “currants caramelised in port” be magically turned into beer in this “tiny universe inside the bottle”? Such questions show that this brewery does not primarily belong to the food industry but instead sees itself as a trailblazer in the realm of flavours. Otz: “We aim to provide an experience. Inspirationally produced beer is a culinary experience.” There is no room for compromise: “We’ve thrown away entire batches because we failed to produce what we envisaged.” Achieving perfection is no reason to stop looking for new ideas either: “We make beer for a season. Then it’s over.”

From local to global

The rock star of the “new age of Swiss beer” is undoubtedly Jérôme Rebetez from Saingelégier, who is anything but introverted. As a 23-year-old oenologist he created one of the first small-scale breweries in 1997 – the Brasserie des Franches-Montagnes (BFM). Today, BFM is a giant amongst dwarfs. However, Rebetez’s approach to brewing is not one bit tamer than when he started out producing a Jurassian synthesis of the arts, bringing together joie de vivre, craftsmanship, concerts and beers with edges and contours – the only thing they cannot be is random.

BFM now exports a quarter of its production abroad. In 2009, the New York Times lauded its Abbey de Saint Bon-Chien beeras being perhaps the best beer in the world. This meant Rebetez had achieved one of his main goals. He had started out with the aim of “creating an artisan, unconventional and defiant beer, a beer with an extremely sophisticated bouquet that was rich on the palate and could easily be compared with the finest wines”. “Abbey de Saint Bon-Chien”, which is matured in oak barrels, comes up to the mark.

What does Rebetez – the successful pioneer of the early days – think of the current crop leading the way? He sees a fast-moving scene with lots of people flying the flag for the new beer culture: “But few of them see themselves as business people.” He himself entered the industry years ago to counter its “extremely boring” character, but voices mild criticism: “I find some of it too experimental.” If a beer is to remain a beer, “then you should be able to drink a whole bottle on your own”. He remains a rebel and is resisting the pressure to innovate: “Four of my very first beers are still our best-selling. I take great pride in that.”

He believes that any brewers able to leave their own mark can look forward to an exciting future. Anyone in their right mind wants genuine choice, he says. This requires original products from authentic companies with a real story. The BFM team are also great storytellers. The immortalised Saint Bon-Chien – the noble, sacred dog – who appears on the label of the much-acclaimed fine beer is not a dog at all. This was the name of Rebetez’s dead brewery cat. The stout Alex le Rouge is also an obituary in the form of a beer in honour of BFM’s former communist brewery technician who even after his retirement continued to potter around and drink in the brewery until his dying day. The Jurassians sometimes like to use wordplay to get one over on the German-speaking Swiss. After deciding to promote a BFM beer in German-speaking Switzerland in the period before Christmas, Rebetez labelled the bottles with the grammatically incorrect expression “Die Bier vom Weihnachten” (the beer of Christmas). In short, four words, two howling errors and a smirking brewer in Saignelégier. His Highway To Helles is also a bit of banter with German-speaking Switzerland. Beer drinkers there often order “ein Helles” (a light beer). He finds the fact that they ask for a beer based on its colour astonishing. If somebody buys a new car, they don’t say “a grey one, please”. Those who do not appreciate his tongue-in-cheek ribbing can turn to one of the other 900 breweries in Switzerland.

Wild yeast

Back to the Gurten, the small mountain situated on the outskirts of Berne. The historic local beer has long since ceased to exist, as already mentioned. However, the 523 team recently began working on a plan hatched over many years to brew a beer based on original recipes from the 1900s – and using local yeast as it should “embody the earth”. They put down a dozen containers containing beer wort on the Gurten to collect wild yeast. The method worked. Promising samples were found in three of the twelve containers, so they decided to carry on collecting the wild yeast. They then carried out weeks of research on the old local recipes and gained new insights into the ingredients commonly used in the past. 523 has not yet decided what to do with the results. At least in this case, the Swiss beer boom will provide an entirely new interpretation of oral history.

The end of the beer cartel

The diversity of the Swiss beer market is explained by the collapse of the Swiss beer cartel. This was established by Swiss breweries in 1935. Distribution areas were defined, the range of beer was limited to a few varieties and it fought against the import of foreign beers. The cartel broke up in 1991 after the departure of three major breweries. The cartel also meant that Swiss beer came to be seen as commonplace. The market was therefore open to new players after 1991. Foreign beers quickly won growing market share and the number of Swiss breweries has increased three-fold between 1991 and today.

Alcohol consumption is falling

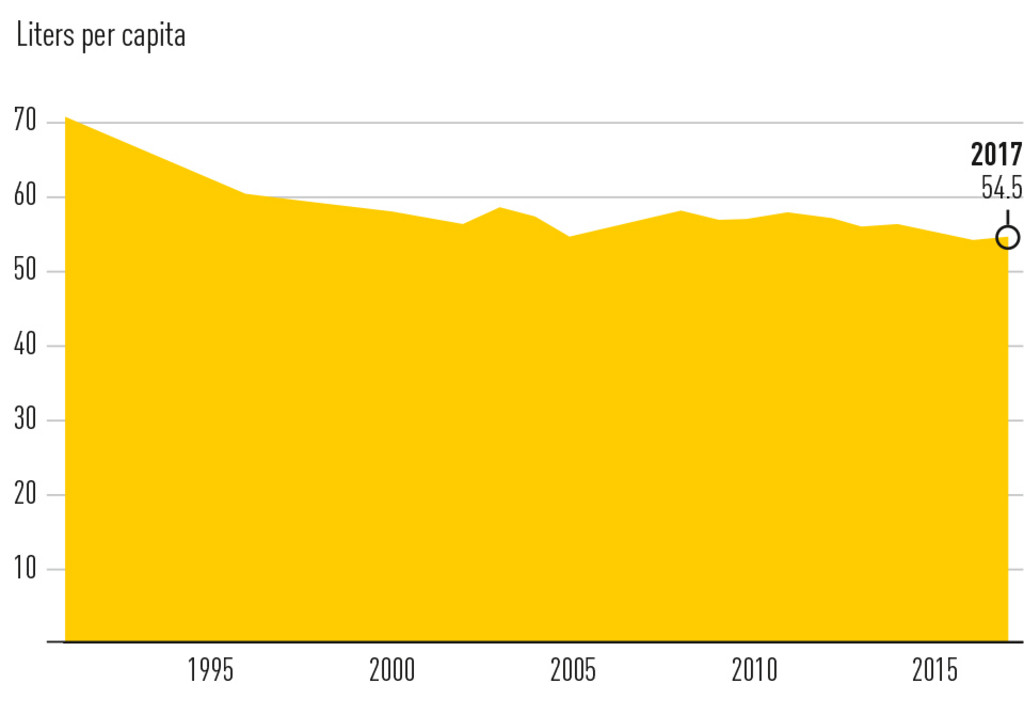

The number of breweries is rising, but beer consumption is in continual decline in Switzerland. In 1990, it stood at around 70 litres a year per inhabitant. Today, it is just over 54 litres. One reason for the decline is the reduction in the blood alcohol limit for driving in 2005 from 0.8 to 0.5 per mille. A general change in society has also taken place. Alcohol is now taboo at the workplace and there is much greater awareness of health in general. The boom in microbreweries is not driving consumption up because they see their beers as an exclusive – and expensive – beverage. They are priced at 5, 10 or in some cases even over 20 Swiss francs a bottle.

Quelle: Eidgenössische Zollverwaltung. Daten

Comments

Comments :