Drums produce an ear-splitting noise. The poems read out in-between can barely be understood. A Russian balalaika orchestra then enters the stage. On the walls hang graphic art by Picasso and posters of futurists. Music by Debussy and Brahms is played on the piano. Dances are stomped on the stage. The audience caterwauls. The students, revellers and dandies call for beer and women’s legs. When the mood threatens to change suddenly, a deathly pale young singer takes to the stage and starts to perform chansons and ballads. Her fragility captivates everyone and momentarily produces quiet.

When Cabaret Voltaire opened its doors on 5 February 1916, it presented itself to the public as a platform for anything and everything. Hugo Ball wanted a “coexistence of possibilities, people and outlooks”, and to that end wrote: “Everyone who wants to contribute something is welcome.” His partner Emmy Hennings sent an appeal for help to a friend in Munich: “If you know any young people who are coming to Zurich, or are already here, who would like to get involved in the cabaret, then please let me know.” The pair had arrived in Switzerland in summer 1915, had made ends meet playing the piano for eight hours a day and with tawdry dance performances at undistinguished cabarets, and finally wanted to do something that matched their artistic ambitions.

A hall with 50 seats stood empty on Spiegelgasse in Zurich’s Niederdorf district. It belonged to the Meierei wine bar and had a short time before housed a cabaret called the Pantagruel. Further immigrants soon joined Hugo Ball and Emmy Hennings. The medical student Richard Huelsenbeck came from Berlin, the Romanian Tristan Tzara had been sent to Zurich to study by his father and Hans Arp got to know Sophie Taeuber at the Galerie Tanner, a modern art venue. Then there were Marcel Janco and the Swiss musician Hans Heusser. Walter Serner was already there. They formed the core group around whom additional guests continually flitted. Picabia, who played an important role in spreading the word about the new movement on his extensive travels, sometimes dropped by.

Discords and simultaneous poetry

They offered a colourful programme every evening except for Fridays. They read texts by authors as diverse as Voltaire and Wedekind. The music ranged from medieval church music to atonal discords. Tzara, Janco and Huelsenbeck performed simultaneous poetry which nobody could understand. There were negro dances and negro music. Janco stopped by one day with masks which the actors used to change their movements. In early summer Hugo Ball took to the stage in a Cubist bishop’s outfit made of cardboard and performed one of his sound poems: “Gadji beri bimbaglandridi lauli lonni cadori”. When Rudolf von Laban opened a dance school in Zurich, his girls made expressive dance one of the key features of evenings at Cabaret Voltaire.

The directness of the physical expression, the overstatement and the search for simplicity and originality were reflected in the picture collages of the artists as well as in Ball’s sound poems and the dances of Mary Wigman, Suzanne Perrottet and Sophie Taeuber. This was about breaking up conventional forms and the search for a new grammar. Describing Taeuber’s dance to the “Song of the Flying Fish and Seahorses”, Ball wrote: “It was a dance full of flashes and edges, full of dazzling light and penetrating intensity. The lines of her body broke up. Each gesture decomposed into a hundred precise, angular and sharp movements.”

The First World War was raging in Europe. While students and foreigners tapped their thighs at Cabaret Voltaire, a million soldiers were slaughtered in the first half of 1916 in the warfare of attrition at Verdun and on the Somme. The euphoria with which some writers and artists had greeted the outbreak of war had long since faded away. Bourgeoisie culture could not prevent the horror. Its values were bankrupt. Nihilism was all that remained. Hugo Ball was well versed in Nietzsche. He took the diagnosis seriously but rejected the pathos. The artists of Cabaret Voltaire saw the old world collapse and worked with its rubble. Through irony, paradox and play on content and forms they could be committed but avoid destruction.

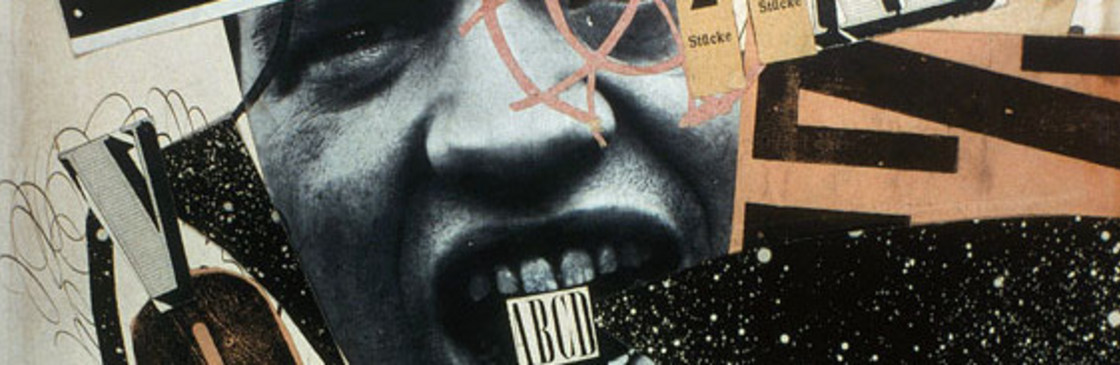

The cabaret stage provided appropriate forms for this. “Educational and artistic ideas as a variety programme – that is our form of Candide against the times,” wrote Ball. The Dadaists were non-political, behaved anarchically and consequently became the most trenchant opposition of their era. Dada discovered the desire for chaos and scandal and developed its own world of forms from this. Its protagonists split language into sound poetry, typeset into a mélange of typographies, images into collages and photo montages, and dance into delicate forms.

A sign of foolish naivety

The term Dada first emerged when Cabaret Voltaire was about to close its doors again. After five months, the performers were exhausted and Ball and Hennings moved back to Ticino. Despite this the term Dada became established. Many myths circulated about its emergence. The most plausible is Hugo Ball’s explanation, which he entered in his diary: “In Romanian, Dada means Yes, Yes, in French it signifies hobby horse. For Germans, it is a sign of foolish naivety and an avaricious bond with the pram.” Several weeks later he made the word public in the “Cabaret Voltaire” anthology. It implied radical negation without having to propose something new. The Dadaists had not exactly invented the word. There was a “lily milk soap” in Zurich sold under the name of Dada by the company Bergmann. That fitted with the fascination that advertising and the media held for the Dadaists.

The blossoming of Dada in Zurich soon came to an end after the war. The soirées, exhibitions and tea parties actually continued until 1920. Public enthusiasm even peaked with the eighth soirée at the Kaufleuten in 1919. Thousands of visitors filled the coffers like never before. But the movement sought other locations. Berlin became a hub for a few years with biting satires against post-war militarism. In Paris, André Breton was interested in Dada until he realised it would not allow him to develop principles for his surrealism. Dada became an international movement which Tristan Tzara was keen to present at the end in his “Dadaglobe” almanac. Philippe Soupault once again clearly outlined what Dada was in his submission: His collage “Dada soulève tout” depicts a port crane lifting up the world. The words “Give Us the Runway and We will Lift the World” appear below it. A tract was published under the title a year later which railed against any form of dogmatism and all artistic attitudes of modernity. “Oui = Non” was the only possible position for Dada.

Gerhard Mack is culture editor at the “NZZ am Sonntag”

Picture The Dadaists discovered the desire for chaos and scandal and developed their own world of forms from this. (Image: Self-portrait by Raoul Hausmann, collage 1923.) Photo: Keystone

Comments

Comments :